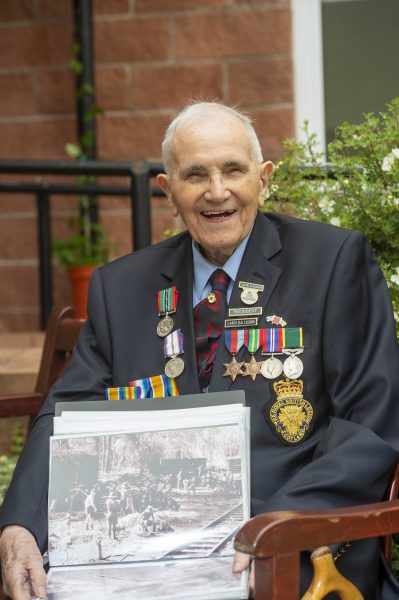

As the country comes together to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day – or VJ Day as it is better known – a 100-year-old veteran who was captured by the Japanese and forced to work on the construction of the infamous Burma railway has spoken movingly about his lost comrades and how he believed he was just weeks from death before the dropping of the Atom Bombs brought the Second World War to an end.

The incredible story of Robert John Ransom – better known as Jack Ransom – will form part of tomorrow’s VJ Day commemorations, which are to be marked by a series of “virtual” events organised by Armed Forces charities Legion Scotland and Poppyscotland, in partnership with the Scottish Government. Programmes will be broadcast live via the charities’ social media channels to mark the milestone anniversary. A virtual Service of Remembrance will be shown from 10:35am, and will be followed at midday by a virtual concert.

On Monday 17 August, which will mark the first full week of the new school term, a live lesson will help to ensure that younger generations have an opportunity to learn more about the significance of VJ Day.

Speaking to Legion Scotland, Mr Ransom described his vivid memories from his time during the six-year conflict. Mr Ransom, who is originally from Peckham, in London, and now lives in Largs, said:

“I joined the Territorial Army at the beginning of 1939. When War was declared on the first Monday of September 1939, I was already in uniform at Woolwich Barracks, in London. I was attached to the 118 Field Regiment Royal Artillery.”

It was two years until Mr Ransom left these shores, as he explains:

“We left the shores of Blighty in November ’41. We were in the first convoy, known as the ‘Secret Convoy’, that was escorted by the American Navy. At that time, America had not joined Britain in the War, but they were escorting British troops. We left Liverpool and we were met halfway across the Atlantic by the Atlantic Fleet of the Americans. In other words, our escort changed from two or three very old destroyers to a complete flotilla that included aircraft carriers and battleships.

“We eventually arrived in Nova Scotia and were transferred to American vessels and we went aboard an American troop ship. And from there we sailed right down the coast of South America calling at Trinidad and then across to South Africa. And when the convoy got to Cape Town that’s when Pearl Harbour happened, which brought America into the War.

“We thought we were going to north Africa, but due to the fact that Japan was now in the War, I think the government was worried about Malaya. The Australian government wanted back-up, so instead we would go to the Far East. We were sent to India for three weeks while they made their mind up. We went back to Bombay and sailed for Singapore, arriving towards the end of January. We never got off the island as the Japanese were too far down and had pushed the Australians back.”

But it wasn’t long before Mr Ransom and his comrades were compelled to surrender… but it was not a decision that was met with approval. He adds:

“I never saw the Japanese until I was taken prisoner on Singapore island. We were given the order to surrender. We didn’t surrender; we were ordered to surrender.

“We didn’t understand while we were surrendering. The reason we were given was that the civilian population in Singapore town were suffering. Eventually, the Japanese moved in, but, before then, we did as much damage to our equipment as we could to make sure we didn’t pass on any vital pieces.

“When they arrived, we were absolutely bewildered. They were small, non-descript looking men, and our first thought was: ‘Why are we surrendering?’ However, the deed had been done. We were marched from Singapore town up to Changhai to be prisoners of war. That commenced my period as a POW, a period which lasted from February 1942 until August 1945.

“For a while in captivity, we led our own lives. We grew vegetables, we chopped down trees for firewood, we got a ration of rice which we cooked for ourselves. We didn’t get any parcels or mail, or anything from the Red Cross whatsoever. We looked after ourselves as best we could.”

However, things would take a dramatic turn for the worse, as Mr Ransom explains:

“It all changed when the Japanese penetrated into Burma. They had to find a way to get supplies to their troops and could only do it via Thailand, so they had to construct the railway from Thailand into Burma. The plans they used were old ones that had been formulated by the British. For the building of that railway they needed labour. They transferred most of the prisoners of war to Thailand to build it.

“The POWs went up to the railway in Thailand in groups and I went up in the final group. By that time, hundreds of POWs that had gone up previously had died from cholera and various other diseases. When I arrived, they needed people to work on the railway at the Burma border, so we marched from the start of the railway up to Burma. It was about 200 miles. Well, some of us got there, some of us didn’t.

“Eventually we got to a small camp and we were put to work building the railway embankment. We were on that for quite a time… After the railway was more or less up and running, we were put on the job of supplying ballasts for the railway, which meant working in quarries breaking up stone, which in itself was a hazardous job. Flints fly into your legs and your arms and your body and these turn into tropical ulcers… not so nice.

“Attempts to escape were made by one or two individuals, but they were caught. But where would you go? There was nothing around for hundreds of miles. Those that were caught were brought back and beheaded. Once the railway was up and running, they needed us somewhere else. Those left were put on trains and taken back before being divided into two lots. One group went to Japan to work in the mines, and the group I was in was sent back to Singapore where I worked for the Japanese digging defence tunnels.”

But Mr Ransom and his comrades then began to get a sense that the tide was turning in favour of the Allies, as he describes:

“By this time, in 1944, the Americans were starting to push back the Japanese. We started to realise that things were not going too well for our captors. So, at least we had a thought of something to look forward to.

“We knew nothing about VE Day and we didn’t know that the Atom Bombs had dropped, but we thought that things might be going our way. I was working on the defence tunnels in Singapore. You worked from daybreak until night. We worked seven days a week apart from one single day when it was the Emperor’s birthday.

“Every morning we were collected by the Japanese guards at dawn, but one morning they didn’t turn up. We didn’t know why. We returned the next morning, but, again, the Japanese didn’t come. Then the rumours started. Somebody said that the Japanese were about to surrender. We didn’t believe it. But eventually, of course, it became true.

“The first sign that I had was a paratrooper walking up the road towards the jail. I said: ‘Good morning!’ I was a scarecrow, I was in rags, no shoes – I only weighed six stone. We were fed on only one bowl of rice a day. I was so pleased to see somebody. Then, suddenly, the rations got better for us. And more clothes were found – mainly coloured T-shirts.

“Eventually, Earl Mountbatten arrived and accepted the surrender of the Japanese. Then he came up to the Changhai jail. We knew he was in charge of everything, so we turned out a Guard of Honour. It must have been the most non-descript Guard of Honour he has ever seen. No two were dressed the same. Some had shoes, some did not. He walked down the Guard of Honour of 90 of us as if he was at Buckingham Palace.

“I had to wait until the end of September for transport, and I came home on a Polish ship. It took a month to get home and we docked at Liverpool. We were kitted out and I got my stripes back again – I was a Sergeant. I was checked by doctors and got away the next morning to King’s Cross. There, we were picked up in cars and taken home. I went up to the front door and my Father opened up. And there I was. Home. I hadn’t been back since 1941.”

And looking towards the 75th anniversary of VJ Day, Mr Ransom has some very poignant thoughts:

“Thinking back the past 75 years to 1945, there are three things that are in my mind. One, I never forget my comrades; those that did not come home. And there were many of them.

“The second thing is, I always think that if it hadn’t been of the dropping of the Atom Bombs I would not have been released in time to save my life, but, of course, in my mind is the thought that by dropping the Atom Bombs all of those civilians – men, women and children – died in Japan. And last thing, now that I am 100 and have received a birthday card from Her Majesty The Queen, I think of the Emperor of Japan who should have also sent me a birthday card. After all, I did work for his grandfather, too.”

Legion Scotland Chief Executive Dr Claire Armstrong said:

“Mr Ransom is well loved and respected amongst our Legion membership and in the community of Largs. It’s easy to see why. His account demonstrates a man of great resilience and humour, who, despite his experiences during the War, has gone on to live a long and fruitful life.

“His story gives great insight into the experience of Prisoners of War and the horrendous conditions they had to endure. And yet he, and many, many others like him, carried on with a spirit of optimism and determination. We are truly grateful for the men and women of the Second World War generation for their service and sacrifice. On the eve of the 75th anniversary of this important milestone in our nation’s history, we are calling on the nation to pause, to remember and to pay tribute to Jack, and so many other like him.”

The Far East campaign began on 7 December 1941 when Japan attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbour. The British colony of Hong Kong was attacked the following day and, over the subsequent weeks, the British retreated to Singapore, where they were forced to surrender with more than 9,000 men killed or wounded. A further 130,000 were captured and became POWs, facing years of appalling conditions.

The Allied fightback began in 1944 and was led by the British Fourteenth Army, stated to be the largest all-volunteer army in history with 2,500,000 men and comprised mainly of units from India and East and West Africa, as well as Britain. The campaign to recapture Burma was one of the longest fought by the British during the War, but they finally entered the capital, Rangoon, on 2 May 1945. Just as they prepared to progress onwards to Malaya and Singapore, the Atom Bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki leading to the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, officially marking the end of the Second World War.